Keith and Christine would love to hear from you with questions, comments, personal news and any news at all from Australia or wherever you are. We will reply to all emails! Please write to either windlechristine@gmail.com or windle.keith@gmail.com

This was to be our last full day in Istanbul – a sad realisation since we have come to love it and can see how much more there would be to explore and know. It would be spent mostly on the other side of the Galata bridge. The plan, which included six major sites some distance from each other, appeared to require super human abilities.

The Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts is in the palace of Ibrahim Pasha, who had started life in Greece and been captured and sold as a slave to the Imperial family. He and Suleyman became friends, he held many official posts and he was given this palace the year before he married Suleyman’s sister. His death in 1536, at the instruction of Suleyman, was supposed to be instigated by Roxelana, who felt that he had too much influence. It is a gracious building with a gardened courtyard in the middle and the perfect setting for the beautiful artefacts, illuminated manuscripts and the carpet display. So much care was taken, the ornamentation is often all over an object and the designs are intricate and repeated.

The carpets were stunning and presented in groups showing the styles developed in particular areas at particular times. Kilims, the flat woven type of carpet, were being made in Anatolia in very early days, but it was not until the Turks migrated here from Central Asia that knotted carpets began to be made. Fine examples exist from the Seljuk period, around the 13th century, with Marco Polo having written of the ones he had seen in Konya. The museum has carpets across the eras, with many from the Ottoman era being absolutely huge. Even to our untrained eyes, it was possible to see the development from two or three colours to a multitude, from simple fairly geometric designs with areas of plain, to the addition of intricate symbolic borders and eventually all over complex, curved designs. I would love to make a carpet, and naturally I want to make one like the glorious 17th century examples that complete the display.

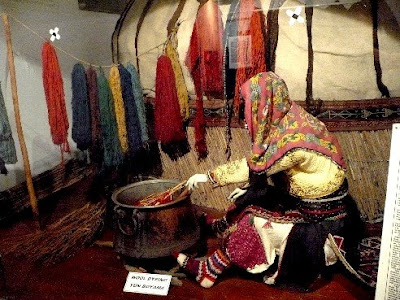

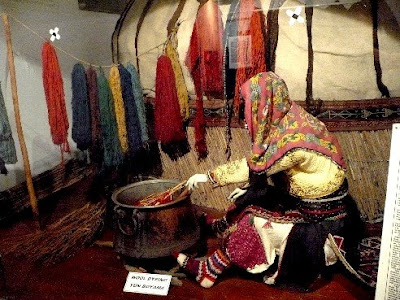

Downstairs we saw the ethnographic display and it was interesting to see goat hair tents and the way of life for nomads. I noted that the women did all the tent erecting, spinning, weaving, cooking, cleaning, milk processing to yoghurt and cheese, dye plant collection, dying, child minding and goodness knows what else. The men were busy with the herds, although women and children also helped. Perhaps the musical instruments, the water pipe and the woollen filled sleeping mats represented how the men filled their time.

Downstairs we saw the ethnographic display and it was interesting to see goat hair tents and the way of life for nomads. I noted that the women did all the tent erecting, spinning, weaving, cooking, cleaning, milk processing to yoghurt and cheese, dye plant collection, dying, child minding and goodness knows what else. The men were busy with the herds, although women and children also helped. Perhaps the musical instruments, the water pipe and the woollen filled sleeping mats represented how the men filled their time.

There was an excellent display on dye plants and how the very vibrant colours were achieved using different plants in different locations. Rooms represented a village house, a wealthy Istanbul house, a dyers cottage and the more traditional lifestyle in a Bursa house, with the contrasts we see in modern Turkey clearly already present in the past.

We caught the tram across the bridge to the Istanbul Modern – a museum of modern art. Keith had to hand in our picnic knives before we could enter, and we left our cameras in the cloakroom since photography was forbidden. We hired audio guides to help us understand the background behind what we were seeing. We learnt that there were few professional artists in the Ottoman era prior to about 1890. There were certainly accomplished artists who were commissioned for set works in specific styles, but painting as a profession had not developed. After this time, artists began to train in Europe and to incorporate and experiment with the ideas bubbling there. Some paintings represented revolutionary and war themes and later works showed impressionist, cubist, abstract and other styles.

We caught the tram across the bridge to the Istanbul Modern – a museum of modern art. Keith had to hand in our picnic knives before we could enter, and we left our cameras in the cloakroom since photography was forbidden. We hired audio guides to help us understand the background behind what we were seeing. We learnt that there were few professional artists in the Ottoman era prior to about 1890. There were certainly accomplished artists who were commissioned for set works in specific styles, but painting as a profession had not developed. After this time, artists began to train in Europe and to incorporate and experiment with the ideas bubbling there. Some paintings represented revolutionary and war themes and later works showed impressionist, cubist, abstract and other styles.

Other exhibitions were of video instalments with an intriguing one showing behaviour regarding personal space in an airport. The people had been filmed and afterwards a halo-like coloured bubble representing an extension of their personas had been added. Self portraits by artists showed both varying styles and self concepts – something representing particular people always having a strong pull for me. Finally, a fantastic design exhibition which covered over a century and placed all kinds of daily items in displays from different cities noted for design. Some of them were London, Vienna, Tokyo, Paris and Los Angeles. We wished that Holly was there to see it.

Reclaiming our knives, and unfortunately the camera memory card filling just at the crucial moment when I was about to capture the guard handing them back, we took another tram to the funicular station. Public transport here is state of the art – all trips are one price (about $A1.10) for all types of transport including ferries, token seller booths are at the stops, you enter using your token to open the gate, you exit to protected areas in the middle of the road for trams and to roadsides for buses and the public transport vehicles just keep on coming. The funicular is like a train pulled up a tunnel in the steep hill by cables.

We walked a long way to the military museum, selected by me not because of my well-known interest in uniforms and weapons, but because it features an Ataturk room. On the way we were subjected to an amazing scam. A shoe shine man passed us and dropped his large shining brush, seemingly not noticing. Keith naturally scooped it up and handed it back. The shoeshine man thanked us, and we set off to the museum. A nice moment and finished in our minds. Seconds later he ran after us and indicated, in both a little English and by body language, that it would be his pleasure to clean Keith’s shoes to express his gratitude. We were in a hurry but it seemed churlish to refuse so Keith proffered his foot, clad in the only pair of shoes he has, which are not shineable. The man dipped a toothbrush into water and rubbed it over Keith’s shoes, meanwhile asking if we had children and telling us about his three, asking where we were going next (Bursa) and saying how he had lived there until, after an accident, he was forced to be a shoeshine man in Istanbul. Keith’s shoes had only taken about 45 seconds after which he indicated that he wanted to give me a shoe shine (shoe wetting) too. Imagine our surprise when we thanked him and he announced that it would be 18 lira ($A15), which he claimed is the cost of a regular double shoe shine. Keith explained that we thought he was doing it for free so he changed to saying that it was for free and that the 18 lira was a present for his children – we have children and we have money. Keith gave him 5 lira for his children under that emotional blackmail attack, while telling the man what he had thought and why he wouldn’t pay more. Eventually the man said "Ok, no problem," and we walked off with a fairly nasty taste in our mouths. This became worse when Keith realised that the whole scenario may have been a set up, right from the dropping of the brush and the setting up of some sort of trust and benign relationship. We wished that we could have watched him unobserved to see if this was indeed his modus operandi and Keith is convinced it was. Later we checked shoe shine prices and our informant laughed at 18 lira for less than two minutes and a little water.

The Military Museum was due to have a band playing, but since we were on a tight schedule we opted to see around first and go out half way through the concert. It was not to be since they only played for half an hour and had finished when we had made it through some memorabilia from Gallipoli and Çanakkale and the hall of Sultans. The portraits of the Sultans showed them all to have raised, curved eyebrows, which gave them all an imperious air, along with a slightly surprised look. It turned out that there had not been a tradition of portrait painting and so at a certain point, an Italian artist had been commissioned to paint everyone to date using a few old stylised drawings as guides. After that it was apparently remarkable that the portraits had shown the sultans in naturalistic poses, such as slightly side-on, or holding a book. I hadn’t even noticed, but it was apparently ‘big time’ to have portrayed a sultan that way. There was an excellent model showing the conquest of Istanbul by Mehmet the Conqueror, with his rollers allowing his ships to go overland and avoid the Genoese chains across the Bosphorus. The enormous chain was also on display, skulking in the corner opposite.

There were so many rooms with well set out, interesting displays of armour, gear related to military horses, arms and various battles and campaigns. The information in English was excellent and full of stories on a grand scale, but also about individuals and their lives. Particularly interesting to us were the World War 1 room, and the video using original film on the battles at Çanakkale and Gallipoli. Watching it, filmed by Turkish men who were risking their lives along with the soldiers, the grainy, jumpy shots with bursts of dust shooting up when bullets hit and wounded soldiers being supported and cared for, with distance shots showing the impossible terrain for an attack and the narrow but incredibly exposed beaches below, with sudden focussing on boyish faces and swinging to the trench lines – I felt the terrible sadness that comes when I see film of our boys there. The Gallipoli campaign, which we commemorate with ANZAC day, is also of great significance here as a victory, and is well known to be of great importance for Australians. There is no side that wins in war – the Turkish losses were colossal, with nearly every family losing a member or close friend.

There were so many rooms with well set out, interesting displays of armour, gear related to military horses, arms and various battles and campaigns. The information in English was excellent and full of stories on a grand scale, but also about individuals and their lives. Particularly interesting to us were the World War 1 room, and the video using original film on the battles at Çanakkale and Gallipoli. Watching it, filmed by Turkish men who were risking their lives along with the soldiers, the grainy, jumpy shots with bursts of dust shooting up when bullets hit and wounded soldiers being supported and cared for, with distance shots showing the impossible terrain for an attack and the narrow but incredibly exposed beaches below, with sudden focussing on boyish faces and swinging to the trench lines – I felt the terrible sadness that comes when I see film of our boys there. The Gallipoli campaign, which we commemorate with ANZAC day, is also of great significance here as a victory, and is well known to be of great importance for Australians. There is no side that wins in war – the Turkish losses were colossal, with nearly every family losing a member or close friend.

Next we visited a room designated to the situation with the Armenians. Could this have been the records no longer on display in Van? There were terrible photos of atrocities carried out by Armenian terrorist gangs against Turks, with some blame being laid at the feet of international powers, who stirred the Armenian unrest and supported their independence battles, for their own ends in weakening Turkey. The brutality was extreme and seemed calculated to cause suffering and give messages way beyond what a quick death would entail. There was no attempt to present any Armenian reasoning or accounts of the time, so it was, as could be expected, one sided. Nevertheless, I thought back to the student in Konya who had told us that he had an Armenian grandmother and that she was a liar. She had told him her version, as one-sided as the one we were reading, but had said that there had been no atrocities committed by any Armenians. If people could acknowledge their group’s shameful behaviour, there would surely have to be more respect and the possibility of a positive future in dealings with the other people. With the ‘all or nothing’ approach, even a grandson’s love cannot transcend his adult understanding of his grandmother’s deception.

Armed with many pamphlets on military matters which the attendant had singled me out to be worthy of, and had gone to a special cabinet to procure, we left when asked to in time for the staff to make a quick get away. There was an enormous revolving 1889 canon in the garden, which turned on a circular track. It required a winch to load the projectile into its retractable barrel. The winch stopped working so Private Soldier Seyid handled and loaded the 276 kilogram projectile from then on.

We had to abandon our visit to the 19th century Dolmabahce Imperial Palace, supposed to be the extreme in over the top decorations, since it was already closing time.

We had to abandon our visit to the 19th century Dolmabahce Imperial Palace, supposed to be the extreme in over the top decorations, since it was already closing time.

We headed east and downhill through some gardens where the magnificent bronze heads of military leaders, including Atatürk, gazed on in wonder as about twelve boys from about 8 – 12 years dived and frolicked in the fountain pool. The bust plinths were used for modesty in divesting clothing and for surreptitious smoking. It was interesting to note that the teenage smokers also engaged in the adult male behaviour of greeting their friends by touching cheeks on each side and linking arms.

Istanbul is well endowed with gardens and parks, so we were able to lollop sideways and down the hill through some connecting ones. The last one before we emerged into the streets had unusual, casually posed sculpted people, who appeared to have been local identities. One was sitting on a wooding bench, holding an instrument.

Istanbul is well endowed with gardens and parks, so we were able to lollop sideways and down the hill through some connecting ones. The last one before we emerged into the streets had unusual, casually posed sculpted people, who appeared to have been local identities. One was sitting on a wooding bench, holding an instrument.

The walk to the park where the two Imperial Köşküs were, seemed elastic, but at last we arrived at the start of the park walls and shortly after that, on the other side of the road, some ornate gates to Ciragan Palace. At the same time, large photos of Atatürk started to appear on the park wall, so we were torn between looking in at the continuing views of the palace or examining the great man himself. Atattürk won. After a while we passed under enormous decorated stone arches over the road, wide enough for the residents at the palace to have strolled over to the Yıldız Park, which were the Imperial gardens.

After a while we passed under enormous decorated stone arches over the road, wide enough for the residents at the palace to have strolled over to the Yıldız Park, which were the Imperial gardens.  They contained two pavilions, which we had come to visit, and in which the Sultans and their retinues could entertain and enjoy themselves. The road into the gardens passed lush green lawns and beautiful shady trees, under which hundreds of fat grey and black birds, like overweight butlers in grey suits, seemed to be smoothing out the already neat grass. We stopped to eat not far from a young father of two children who was on a date with a giggly young girl who was evidently not the children’s mother. At two and three years old, the boys continually ran off onto the road and were sometimes noticed and hauled back by the amorous adults. At one stage the three-year old ran up to a man walking by with an ice-cream, gestured and grunted in and an agitated way, and fell on the ice-cream with gusto when the man handed it over. The father looked up and called out his thanks.

They contained two pavilions, which we had come to visit, and in which the Sultans and their retinues could entertain and enjoy themselves. The road into the gardens passed lush green lawns and beautiful shady trees, under which hundreds of fat grey and black birds, like overweight butlers in grey suits, seemed to be smoothing out the already neat grass. We stopped to eat not far from a young father of two children who was on a date with a giggly young girl who was evidently not the children’s mother. At two and three years old, the boys continually ran off onto the road and were sometimes noticed and hauled back by the amorous adults. At one stage the three-year old ran up to a man walking by with an ice-cream, gestured and grunted in and an agitated way, and fell on the ice-cream with gusto when the man handed it over. The father looked up and called out his thanks.

The path was steep, but the promise of a lake and the pavilion only ten minutes away spurred us on. The Cadır Köşkü was fairly low key for the Sultans, but set in a very picturesque spot beside an ornamental lake. Ducks were making their way up into their house set in the water and the sound of the fountain called on us to stop and relax. We ignored the call because we wanted to see the other pavilion, the Malta Köşkü, where Sultan Murat V and his family were imprisoned after he was deposed. He had only ruled for 93 days in 1876. This was a prettier building and set in a spot with a glorious view over the Bosphorus. We peeped inside the now café and it was clearly decorated in a very ornate and imperial style.

Walking back, we kept to the side of the park road to dodge the endless taxis carrying one young woman each and the few cars full of young men. There must have been some party or disco venue up there somewhere. Night was well and truly falling so we tried for the ferry, and then decided that the tram would take us closest to our hotel. That gave us another couple of kilometres to walk to the end of the tramline. Once on the tram, we whizzed over the distances that would have taken us so long to cover and were soon back near the Blue Mosque, now referred to by me as ‘the dear old Blue Mosque’. It was after nine but we loitered, admiring a fountain that we hadn’t seen before, a view that we hadn’t savoured. Finally we closed our hotel door on the day and virtually on our visit to Istanbul.

This was to be our last full day in Istanbul – a sad realisation since we have come to love it and can see how much more there would be to explore and know. It would be spent mostly on the other side of the Galata bridge. The plan, which included six major sites some distance from each other, appeared to require super human abilities.

The Museum of Turkish and Islamic Arts is in the palace of Ibrahim Pasha, who had started life in Greece and been captured and sold as a slave to the Imperial family. He and Suleyman became friends, he held many official posts and he was given this palace the year before he married Suleyman’s sister. His death in 1536, at the instruction of Suleyman, was supposed to be instigated by Roxelana, who felt that he had too much influence. It is a gracious building with a gardened courtyard in the middle and the perfect setting for the beautiful artefacts, illuminated manuscripts and the carpet display. So much care was taken, the ornamentation is often all over an object and the designs are intricate and repeated.

The carpets were stunning and presented in groups showing the styles developed in particular areas at particular times. Kilims, the flat woven type of carpet, were being made in Anatolia in very early days, but it was not until the Turks migrated here from Central Asia that knotted carpets began to be made. Fine examples exist from the Seljuk period, around the 13th century, with Marco Polo having written of the ones he had seen in Konya. The museum has carpets across the eras, with many from the Ottoman era being absolutely huge. Even to our untrained eyes, it was possible to see the development from two or three colours to a multitude, from simple fairly geometric designs with areas of plain, to the addition of intricate symbolic borders and eventually all over complex, curved designs. I would love to make a carpet, and naturally I want to make one like the glorious 17th century examples that complete the display.

Downstairs we saw the ethnographic display and it was interesting to see goat hair tents and the way of life for nomads. I noted that the women did all the tent erecting, spinning, weaving, cooking, cleaning, milk processing to yoghurt and cheese, dye plant collection, dying, child minding and goodness knows what else. The men were busy with the herds, although women and children also helped. Perhaps the musical instruments, the water pipe and the woollen filled sleeping mats represented how the men filled their time.

Downstairs we saw the ethnographic display and it was interesting to see goat hair tents and the way of life for nomads. I noted that the women did all the tent erecting, spinning, weaving, cooking, cleaning, milk processing to yoghurt and cheese, dye plant collection, dying, child minding and goodness knows what else. The men were busy with the herds, although women and children also helped. Perhaps the musical instruments, the water pipe and the woollen filled sleeping mats represented how the men filled their time.There was an excellent display on dye plants and how the very vibrant colours were achieved using different plants in different locations. Rooms represented a village house, a wealthy Istanbul house, a dyers cottage and the more traditional lifestyle in a Bursa house, with the contrasts we see in modern Turkey clearly already present in the past.

We caught the tram across the bridge to the Istanbul Modern – a museum of modern art. Keith had to hand in our picnic knives before we could enter, and we left our cameras in the cloakroom since photography was forbidden. We hired audio guides to help us understand the background behind what we were seeing. We learnt that there were few professional artists in the Ottoman era prior to about 1890. There were certainly accomplished artists who were commissioned for set works in specific styles, but painting as a profession had not developed. After this time, artists began to train in Europe and to incorporate and experiment with the ideas bubbling there. Some paintings represented revolutionary and war themes and later works showed impressionist, cubist, abstract and other styles.

We caught the tram across the bridge to the Istanbul Modern – a museum of modern art. Keith had to hand in our picnic knives before we could enter, and we left our cameras in the cloakroom since photography was forbidden. We hired audio guides to help us understand the background behind what we were seeing. We learnt that there were few professional artists in the Ottoman era prior to about 1890. There were certainly accomplished artists who were commissioned for set works in specific styles, but painting as a profession had not developed. After this time, artists began to train in Europe and to incorporate and experiment with the ideas bubbling there. Some paintings represented revolutionary and war themes and later works showed impressionist, cubist, abstract and other styles.Other exhibitions were of video instalments with an intriguing one showing behaviour regarding personal space in an airport. The people had been filmed and afterwards a halo-like coloured bubble representing an extension of their personas had been added. Self portraits by artists showed both varying styles and self concepts – something representing particular people always having a strong pull for me. Finally, a fantastic design exhibition which covered over a century and placed all kinds of daily items in displays from different cities noted for design. Some of them were London, Vienna, Tokyo, Paris and Los Angeles. We wished that Holly was there to see it.

Reclaiming our knives, and unfortunately the camera memory card filling just at the crucial moment when I was about to capture the guard handing them back, we took another tram to the funicular station. Public transport here is state of the art – all trips are one price (about $A1.10) for all types of transport including ferries, token seller booths are at the stops, you enter using your token to open the gate, you exit to protected areas in the middle of the road for trams and to roadsides for buses and the public transport vehicles just keep on coming. The funicular is like a train pulled up a tunnel in the steep hill by cables.

We walked a long way to the military museum, selected by me not because of my well-known interest in uniforms and weapons, but because it features an Ataturk room. On the way we were subjected to an amazing scam. A shoe shine man passed us and dropped his large shining brush, seemingly not noticing. Keith naturally scooped it up and handed it back. The shoeshine man thanked us, and we set off to the museum. A nice moment and finished in our minds. Seconds later he ran after us and indicated, in both a little English and by body language, that it would be his pleasure to clean Keith’s shoes to express his gratitude. We were in a hurry but it seemed churlish to refuse so Keith proffered his foot, clad in the only pair of shoes he has, which are not shineable. The man dipped a toothbrush into water and rubbed it over Keith’s shoes, meanwhile asking if we had children and telling us about his three, asking where we were going next (Bursa) and saying how he had lived there until, after an accident, he was forced to be a shoeshine man in Istanbul. Keith’s shoes had only taken about 45 seconds after which he indicated that he wanted to give me a shoe shine (shoe wetting) too. Imagine our surprise when we thanked him and he announced that it would be 18 lira ($A15), which he claimed is the cost of a regular double shoe shine. Keith explained that we thought he was doing it for free so he changed to saying that it was for free and that the 18 lira was a present for his children – we have children and we have money. Keith gave him 5 lira for his children under that emotional blackmail attack, while telling the man what he had thought and why he wouldn’t pay more. Eventually the man said "Ok, no problem," and we walked off with a fairly nasty taste in our mouths. This became worse when Keith realised that the whole scenario may have been a set up, right from the dropping of the brush and the setting up of some sort of trust and benign relationship. We wished that we could have watched him unobserved to see if this was indeed his modus operandi and Keith is convinced it was. Later we checked shoe shine prices and our informant laughed at 18 lira for less than two minutes and a little water.

The Military Museum was due to have a band playing, but since we were on a tight schedule we opted to see around first and go out half way through the concert. It was not to be since they only played for half an hour and had finished when we had made it through some memorabilia from Gallipoli and Çanakkale and the hall of Sultans. The portraits of the Sultans showed them all to have raised, curved eyebrows, which gave them all an imperious air, along with a slightly surprised look. It turned out that there had not been a tradition of portrait painting and so at a certain point, an Italian artist had been commissioned to paint everyone to date using a few old stylised drawings as guides. After that it was apparently remarkable that the portraits had shown the sultans in naturalistic poses, such as slightly side-on, or holding a book. I hadn’t even noticed, but it was apparently ‘big time’ to have portrayed a sultan that way. There was an excellent model showing the conquest of Istanbul by Mehmet the Conqueror, with his rollers allowing his ships to go overland and avoid the Genoese chains across the Bosphorus. The enormous chain was also on display, skulking in the corner opposite.

There were so many rooms with well set out, interesting displays of armour, gear related to military horses, arms and various battles and campaigns. The information in English was excellent and full of stories on a grand scale, but also about individuals and their lives. Particularly interesting to us were the World War 1 room, and the video using original film on the battles at Çanakkale and Gallipoli. Watching it, filmed by Turkish men who were risking their lives along with the soldiers, the grainy, jumpy shots with bursts of dust shooting up when bullets hit and wounded soldiers being supported and cared for, with distance shots showing the impossible terrain for an attack and the narrow but incredibly exposed beaches below, with sudden focussing on boyish faces and swinging to the trench lines – I felt the terrible sadness that comes when I see film of our boys there. The Gallipoli campaign, which we commemorate with ANZAC day, is also of great significance here as a victory, and is well known to be of great importance for Australians. There is no side that wins in war – the Turkish losses were colossal, with nearly every family losing a member or close friend.

There were so many rooms with well set out, interesting displays of armour, gear related to military horses, arms and various battles and campaigns. The information in English was excellent and full of stories on a grand scale, but also about individuals and their lives. Particularly interesting to us were the World War 1 room, and the video using original film on the battles at Çanakkale and Gallipoli. Watching it, filmed by Turkish men who were risking their lives along with the soldiers, the grainy, jumpy shots with bursts of dust shooting up when bullets hit and wounded soldiers being supported and cared for, with distance shots showing the impossible terrain for an attack and the narrow but incredibly exposed beaches below, with sudden focussing on boyish faces and swinging to the trench lines – I felt the terrible sadness that comes when I see film of our boys there. The Gallipoli campaign, which we commemorate with ANZAC day, is also of great significance here as a victory, and is well known to be of great importance for Australians. There is no side that wins in war – the Turkish losses were colossal, with nearly every family losing a member or close friend.Next we visited a room designated to the situation with the Armenians. Could this have been the records no longer on display in Van? There were terrible photos of atrocities carried out by Armenian terrorist gangs against Turks, with some blame being laid at the feet of international powers, who stirred the Armenian unrest and supported their independence battles, for their own ends in weakening Turkey. The brutality was extreme and seemed calculated to cause suffering and give messages way beyond what a quick death would entail. There was no attempt to present any Armenian reasoning or accounts of the time, so it was, as could be expected, one sided. Nevertheless, I thought back to the student in Konya who had told us that he had an Armenian grandmother and that she was a liar. She had told him her version, as one-sided as the one we were reading, but had said that there had been no atrocities committed by any Armenians. If people could acknowledge their group’s shameful behaviour, there would surely have to be more respect and the possibility of a positive future in dealings with the other people. With the ‘all or nothing’ approach, even a grandson’s love cannot transcend his adult understanding of his grandmother’s deception.

Armed with many pamphlets on military matters which the attendant had singled me out to be worthy of, and had gone to a special cabinet to procure, we left when asked to in time for the staff to make a quick get away. There was an enormous revolving 1889 canon in the garden, which turned on a circular track. It required a winch to load the projectile into its retractable barrel. The winch stopped working so Private Soldier Seyid handled and loaded the 276 kilogram projectile from then on.

We had to abandon our visit to the 19th century Dolmabahce Imperial Palace, supposed to be the extreme in over the top decorations, since it was already closing time.

We had to abandon our visit to the 19th century Dolmabahce Imperial Palace, supposed to be the extreme in over the top decorations, since it was already closing time.We headed east and downhill through some gardens where the magnificent bronze heads of military leaders, including Atatürk, gazed on in wonder as about twelve boys from about 8 – 12 years dived and frolicked in the fountain pool. The bust plinths were used for modesty in divesting clothing and for surreptitious smoking. It was interesting to note that the teenage smokers also engaged in the adult male behaviour of greeting their friends by touching cheeks on each side and linking arms.

Istanbul is well endowed with gardens and parks, so we were able to lollop sideways and down the hill through some connecting ones. The last one before we emerged into the streets had unusual, casually posed sculpted people, who appeared to have been local identities. One was sitting on a wooding bench, holding an instrument.

Istanbul is well endowed with gardens and parks, so we were able to lollop sideways and down the hill through some connecting ones. The last one before we emerged into the streets had unusual, casually posed sculpted people, who appeared to have been local identities. One was sitting on a wooding bench, holding an instrument.The walk to the park where the two Imperial Köşküs were, seemed elastic, but at last we arrived at the start of the park walls and shortly after that, on the other side of the road, some ornate gates to Ciragan Palace. At the same time, large photos of Atatürk started to appear on the park wall, so we were torn between looking in at the continuing views of the palace or examining the great man himself. Atattürk won.

After a while we passed under enormous decorated stone arches over the road, wide enough for the residents at the palace to have strolled over to the Yıldız Park, which were the Imperial gardens.

After a while we passed under enormous decorated stone arches over the road, wide enough for the residents at the palace to have strolled over to the Yıldız Park, which were the Imperial gardens.  They contained two pavilions, which we had come to visit, and in which the Sultans and their retinues could entertain and enjoy themselves. The road into the gardens passed lush green lawns and beautiful shady trees, under which hundreds of fat grey and black birds, like overweight butlers in grey suits, seemed to be smoothing out the already neat grass. We stopped to eat not far from a young father of two children who was on a date with a giggly young girl who was evidently not the children’s mother. At two and three years old, the boys continually ran off onto the road and were sometimes noticed and hauled back by the amorous adults. At one stage the three-year old ran up to a man walking by with an ice-cream, gestured and grunted in and an agitated way, and fell on the ice-cream with gusto when the man handed it over. The father looked up and called out his thanks.

They contained two pavilions, which we had come to visit, and in which the Sultans and their retinues could entertain and enjoy themselves. The road into the gardens passed lush green lawns and beautiful shady trees, under which hundreds of fat grey and black birds, like overweight butlers in grey suits, seemed to be smoothing out the already neat grass. We stopped to eat not far from a young father of two children who was on a date with a giggly young girl who was evidently not the children’s mother. At two and three years old, the boys continually ran off onto the road and were sometimes noticed and hauled back by the amorous adults. At one stage the three-year old ran up to a man walking by with an ice-cream, gestured and grunted in and an agitated way, and fell on the ice-cream with gusto when the man handed it over. The father looked up and called out his thanks.The path was steep, but the promise of a lake and the pavilion only ten minutes away spurred us on. The Cadır Köşkü was fairly low key for the Sultans, but set in a very picturesque spot beside an ornamental lake. Ducks were making their way up into their house set in the water and the sound of the fountain called on us to stop and relax. We ignored the call because we wanted to see the other pavilion, the Malta Köşkü, where Sultan Murat V and his family were imprisoned after he was deposed. He had only ruled for 93 days in 1876. This was a prettier building and set in a spot with a glorious view over the Bosphorus. We peeped inside the now café and it was clearly decorated in a very ornate and imperial style.

Walking back, we kept to the side of the park road to dodge the endless taxis carrying one young woman each and the few cars full of young men. There must have been some party or disco venue up there somewhere. Night was well and truly falling so we tried for the ferry, and then decided that the tram would take us closest to our hotel. That gave us another couple of kilometres to walk to the end of the tramline. Once on the tram, we whizzed over the distances that would have taken us so long to cover and were soon back near the Blue Mosque, now referred to by me as ‘the dear old Blue Mosque’. It was after nine but we loitered, admiring a fountain that we hadn’t seen before, a view that we hadn’t savoured. Finally we closed our hotel door on the day and virtually on our visit to Istanbul.

Istanbul is the only Turkish city in which we have seen buskers - and not many here either.

Istanbul is the only Turkish city in which we have seen buskers - and not many here either.

No comments:

Post a Comment