On our way through the streets of Chake Chake to the other part of our hotel to have breakfast, we called at a tour office to find out about prices. A man there said that he was not the owner, who was not in, and to call back later. We walked down to our hotel, handed in our breakfast card and sat down to wait. The man we had spoken to, Nasa, had followed us and now asked permission to talk to us. It turned out that he was a tour operator with his own business, but it would not have been correct to tell us that in another tour operator’s office. Also, he wanted to know if we had started to negotiate tours with anyone else, because, if we had, then he was honour bound to withdraw. We said that we had agreed for Ali, who had driven us from the airport, to come and tell us about what he could offer, and that we had a friend who we were hoping to spend some time with too. Ali was a taxi driver, not a tour operator, so he, Nasa, was free to speak to us about what he could offer, if we wished. There could have been no greater contrast to the business manners of Arusha than if we had flown to the moon.

While Nasa outlined his options and prices, Ali arrived. Nasa explained his presence in his role of licensed tour operator, and Ali said that he had told us where we could find the tour offices. We said that that was correct, clearing Ali of stepping on toes. Ali withdrew a few paces and gazed over the balcony at the scenery. After Nasa had left us, with the polite request to please consider his offers, Ali put his offers. He told us that as a taxi driver, he was able to drive individuals or small groups all over the island, and that since he was very knowledgeable about the history, geography and nature of Pemba, he could explain things as he drove. He also had a friend with a boat if we wanted a water taxi service to Misali Island to go snorkelling or diving on the reef. Ali was not at all pushy either.

The three Norwegians, Janette and Runard, who work off shore and have a month on and a month off, and Kjersti, who is a kindergarten teacher, came in at this point, and went over all the offers that we had sussed out. Mzee arrived and said that he had nothing on and would be able to take us around for a couple of days. We decided that we would all take up Mzee’s offer of going to Misali Island tomorrow on a boat that Mzee’s used to own and to which he has ready access, at ‘mates’ rates’, and that today the others would go on a tour to the Northern beach with Ali, and that we would do something with Mzee. Mzee went off to borrow his uncle’s car. He has shipped his car out from England, but it was still in a container at Dar es Salaam, awaiting transfer to Pemba.

Mzee was born on Pemba and his family still lives there. He worked with our friend, Michael, who managed a diving business for a while in Chake Chake. Mzee’s English wife, Dianne, had met both Mzee and Michael when she had worked as a VSO teacher, in a role of training teachers. Our niece, Rosie, had been helped by Michael when she was on Pemba and they had become friends. Michael had visited Keith’s sister and family in Australia. Now Michael was back in Barnsley in England, where we had met him while visiting our son Rohan, as a contact through Rosie. He had hosted a dinner where we had met Mzee and Dianne. It is such a strange pathway of connections and of the chance of people being in the same place at the same time, but that was how we came to know Mzee and to be about to go on an outing with him on his home island. Mzee’s parting words to us in England had been, “Tell anyone that you want to see me, Mzee, and they will know me. Any taxi driver will know me and you will be able to find me.” This turned out to be highly likely, since a trip with Mzee involved lots of stops to greet people and to have catch up chats. He is very friendly and has a wide network of friends all over the island. When we were in more remote areas, he regularly stopped for a brief chat and he said that that is how people are here, that you never know when you will need them to help you or when you will need to help them, so it is normal to develop good relations with everyone. What a refreshing philosophy and how enjoyable it was to see it in practice.

First Mzee drove us down to Wesha, where we searched for Mustafa, the new owner of the boat, who was not at home. The port had a jetty and many small boats sitting in the tidal mud flats. The message about the boat was left, and we went back to our Annexe for our bathers, since we too were off to the northern beach.

Chake Chake is a Muslim town, and traditional Muslim clothes are worn, albeit with a colourful African touch. Along with Zanzibar and the Eastern coast, it has been part of a trading group that extended as far as Indonesia, so while it has African roots, there has been centuries long influence from other places.

We edged around cows pulling little carts with produce and building materials on them, soon leaving the town for valleys lush with banana palms and crops. We passed many small villages, with many of them looking very clean and tidy. Young children waved, and Mzee tooted every time we came upon walkers or cyclists, to say hello and to warn them of our coming. We stopped at Konde to buy supplies for lunch – little loaves of bread, tomatoes, onions, chips, cabbage, a coconut and some drinks. It was a market town with many food stalls as well as clothing for sale. The tomatoes were displayed in handful sized piles, and we bought two piles.

Mzee opened the coconut by banging it on a rock, and then using a knife to lift out the flesh. It was divine, and I wished that we had bought two.

Mzee opened the coconut by banging it on a rock, and then using a knife to lift out the flesh. It was divine, and I wished that we had bought two.After Konde, we reached the last police station before the rainforest, where all vehicles had to register that they were going in and anyone intending to walk in or visit the forest had to pay. It did not cost anything to pass through to the northern beaches. Mzee bought a bag of sugar cane for us to try. The sugar cane stalk is peeled, and then cut into pieces about two centimetres long. You bite on them and suck the sweet juice out, and discard the fibrous matter that is left. It was too sickly sweet for me but Keith liked it.

We passed through more villages throughout the day, with the main crops being sweet potatoes, cassava, coconuts, bananas, rubber, sugar cane and pineapples. There were no fences between the crops. Cows with humps on their shoulders grazed in groups in fields where crops had been harvested and on roadsides. Quite a few of the houses had thatched rooves, using the palm leaves. Tarpaulins lay on the ground in front of some houses, with millions of tiny clove buds drying; a surviving part of the spice trade for which the island used to be famous. Slaves were used to work the old plantations, especially for the very labour intensive picking of the clove buds since the trees are quite big. Spices are still grown and oils are distilled but the trade does not dominate the economy as it once did. It is a very important aspect of the tourist trade, but not one that we explored on this visit.

The Ngezi Rainforest is exactly that, and no sooner had we entered it, than it started to rain. A narrow road wound through it, with locals riding their bikes or walking along having to watch out for cars. We scanned the trees for monkeys, but didn’t see any.

As we left the rain forest, the weather cleared and by the time we drove out of the trees and virtually onto the sand of an idyllic beach, it was sunny again. Ali and our Norwegian friends were just heading off to Manta Reef, another beach further on.

As we left the rain forest, the weather cleared and by the time we drove out of the trees and virtually onto the sand of an idyllic beach, it was sunny again. Ali and our Norwegian friends were just heading off to Manta Reef, another beach further on.

We swam before lunch, in crystal clear waters that were warm. A few small waisted jelly fish with stripes on them moved with the tide near the shore. I could have stayed in the water for ever, but I was conscious of the others waiting and called it quits after about an hour.

We swam before lunch, in crystal clear waters that were warm. A few small waisted jelly fish with stripes on them moved with the tide near the shore. I could have stayed in the water for ever, but I was conscious of the others waiting and called it quits after about an hour.

A little further along the beach a small group of children appeared to be having a swim and a play in the water with the family bull calf. After half an hour one of the boys walked the young bull past us on his way home.

We dressed and drove to Manta Reef, along dusty rural tracks.

We dressed and drove to Manta Reef, along dusty rural tracks.The Lodge at Manta Reef was a very up-market venue, set on a stretch of perfect beach with a coral reef nearby. A guard opened the gates to let us in. Ali and the others were just finishing their lunch, and we joined them for a walk down to the beach and along to the cave where slaves had once been hidden.

The cave was set back a bit, and was in behind a wide overhanging ledge. I thought that Ali said that they had kept the slaves on a carpeted area, but given the general treatment of the slaves that we were later to learn about, I must have misheard. Originally the slave trade went on as a ‘legitimate’ activity, but once it was abolished, it continued in a clandestine way for many years, hence the need for hiding the slaves before they were transported to Mombassa.

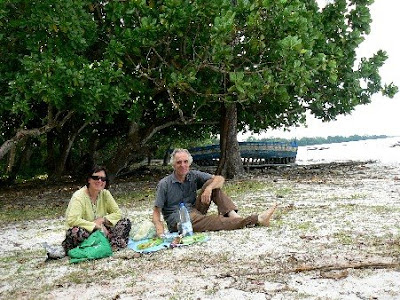

The cave was set back a bit, and was in behind a wide overhanging ledge. I thought that Ali said that they had kept the slaves on a carpeted area, but given the general treatment of the slaves that we were later to learn about, I must have misheard. Originally the slave trade went on as a ‘legitimate’ activity, but once it was abolished, it continued in a clandestine way for many years, hence the need for hiding the slaves before they were transported to Mombassa.We drove back to the beach for our picnic, and as we passed though some farms, Mzee stopped where some men had the most enormous fish hanging up on some scales in a tree. He chatted to them and bought some smaller fish, which were wrapped in banana leaves. There is no excessive, non-recyclable packaging here.

During the trip back, we stopped for Keith to take a photo, and a man seemed to challenge Mzee about whether we had paid to do more than simply drive through the forest. I asked Mzee about it but he just said that the man was crazy. We did stop taking obvious photos.

During the trip back, we stopped for Keith to take a photo, and a man seemed to challenge Mzee about whether we had paid to do more than simply drive through the forest. I asked Mzee about it but he just said that the man was crazy. We did stop taking obvious photos.Back in town we saw the others and Ali – Chake Chake is not very big and the chances of seeing everyone again are high. We finalised arrangements for the trip to Masali Island, and the Norwegians went off with Mzee to find a bar. Being a Muslim town, alcohol is not served. A couple of bars were known to produce it if asked, however the Norwegians said that when they took a photo of their group having a drink with Mzee, the proprietor asked them to delete the photo in case he got into trouble.

We went back to our annexe, and later joined the Norwegians at another hotel for dinner. Unfortunately, the waiter said that he could not cater for vegetarians, so we had a cup of tea. The tea was the most expensive we have ever had in Tanzania, and we wondered if the price was the result of Keith absent mindedly asking for beer.

Back to our hotel, where the chef was a genius, we had a delicious meal and talked to Jane. Her money was all frozen in Iceland, where the banks had been said to be bullet proof. She tried to recruit me to work for VSO, and in another life I would have been very tempted. Actually, I was anyway. Her explanation of aid agencies not placing teachers in classes, where their influence is short term and minor, but in roles of training trainers such as she was doing, made sense.

On our way home, we are struck by the benign nature of the people out on the streets, eating at little candle lit tables or standing around in groups talking. A man jumped up and joined us, asking us in English where we were from, what we were doing and so on. The conversation seemed reasonable, with the lack of understanding or follow up of our answers being put down to poor language skills. He simply seemed like a friendly man. I noticed an Asian man, sitting on the kerb side in front of his little grocery with his children, watching us intently. We stepped onto the stone across the drain that led to our annexe and said ‘Goodbye’ to the man who had accompanied us. He followed us into the downstairs shopping section, and then retreated to the street. We climbed on to our eyrie to go to sleep.

We were not sure whether or not these rubber trees were still being used commercially.

This little gecko was having a stroll around our hotel room.

This little gecko was having a stroll around our hotel room.

No comments:

Post a Comment